Bhumibol thus became a substituted national identity, a substituted nationalism.

(ขอ

อภัย ยังไม่มีเวลาแปลไทย สำหรับท่านที่ไม่ถนัดภาษาอังกฤษ ตัว "ฐาน" หรือ

premise ของการวิเคราะห์นี้คือ เมื่อมีการรวมกันเป็นกลุ่มคน โดยเฉพาะเป็น

"สังคม" หรือรัฐชาติสมัยใหม่ มีความจำเป็นที่จะเกิด a sense of collective

identity หรือ "ความรู้สึกในเชิงอัตลักษณ์หมู่")

After the formal end of mass migration of Chinese in the 1950s, it took about a generation, some 30 years, for social, cultural division along ethnic lines to fundamentally disappear. The initial industrialization in the 1960s and 1970s, the end of the civil war with the Communist Party in the early 1980s, the opening of diplomatic relation with mainland China in the mid-1970s all contributed to this disappearance. Towards the end of the 1980s and especially in the 1990s, there emerged, for the first time, a ‘nation’- a ‘Thai nation’ in which a stratum of Sino-Thai bourgeoisie played the leading role. This whole stratum no longer appeared or was regarded as ‘Chinese’ or ‘chek’ but as ‘Thai’. Because of their lack of real historical roots, of their own identity – they could not possibly ‘relate to’ the too far away Chinese heritage of their ancestors – they therefore ‘adopted’ King Bhumibol as their identity. It was this social stratum that formed the social basis of a phenomenon I call a ‘Mass Monarchy’ or the Rise of King Bhumibol.

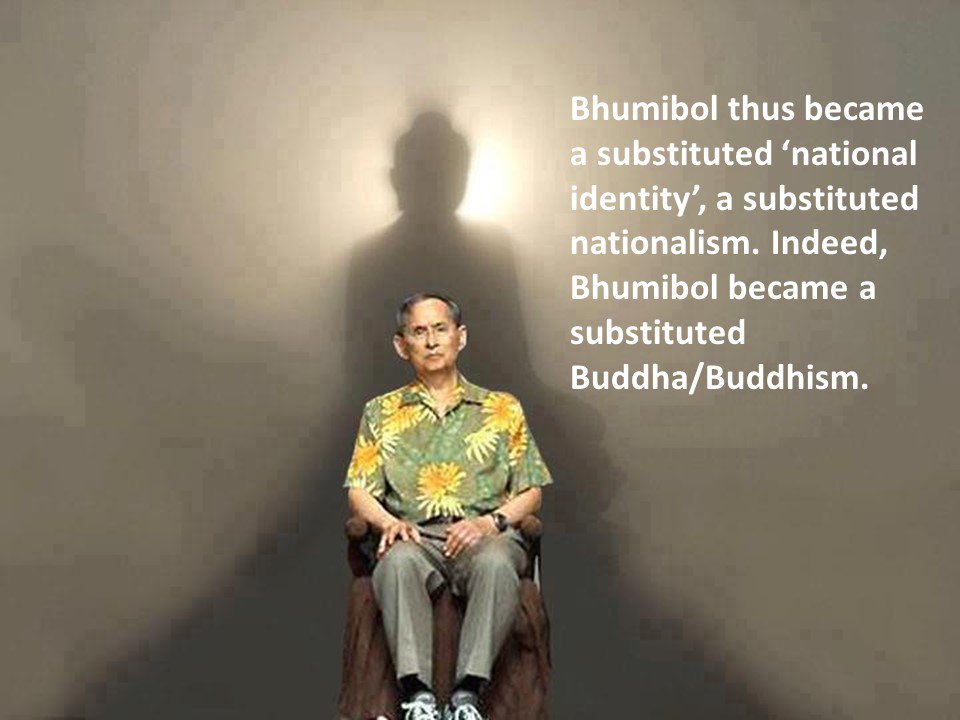

Bhumibol thus became a substituted ‘national identity’, a substituted nationalism. Indeed, Bhumibol became a substituted Buddha/Buddhism (a substituted religion).

After the formal end of mass migration of Chinese in the 1950s, it took about a generation, some 30 years, for social, cultural division along ethnic lines to fundamentally disappear. The initial industrialization in the 1960s and 1970s, the end of the civil war with the Communist Party in the early 1980s, the opening of diplomatic relation with mainland China in the mid-1970s all contributed to this disappearance. Towards the end of the 1980s and especially in the 1990s, there emerged, for the first time, a ‘nation’- a ‘Thai nation’ in which a stratum of Sino-Thai bourgeoisie played the leading role. This whole stratum no longer appeared or was regarded as ‘Chinese’ or ‘chek’ but as ‘Thai’. Because of their lack of real historical roots, of their own identity – they could not possibly ‘relate to’ the too far away Chinese heritage of their ancestors – they therefore ‘adopted’ King Bhumibol as their identity. It was this social stratum that formed the social basis of a phenomenon I call a ‘Mass Monarchy’ or the Rise of King Bhumibol.

Bhumibol thus became a substituted ‘national identity’, a substituted nationalism. Indeed, Bhumibol became a substituted Buddha/Buddhism (a substituted religion).

Inga kommentarer:

Skicka en kommentar